Rother Local Plan 2020-2040 (Regulation 18)

4. Live Well Locally

(11) 4.1 The 'Live Well Locally' concept as an overall priority of the Local Plan underscores Rother's dedication to cultivating healthy, sustainable, and inclusive communities that support residents across the age spectrum. Live Well Locally aims to create an environment where individuals of all ages can live, work, and play with dignity and independence. Rother seeks to foster a dynamic and vibrant community that values diversity and intergenerational connections.

(1) 4.2 This overall priority envisions a network of mixed-use and adaptable places which promote happiness, health and wellbeing, foster social interaction, reduce health inequalities, encourage active living, and enhance overall quality of life. They will be resilient to the effects of climate change while respecting the unique context and character of our district.

(3) 4.3 The approach is to create inclusive 'connected and compact neighbourhoods' in our towns, and 'village clusters' in our rural locations, with inspiring public spaces where people can meet most of their daily needs within a reasonable distance of their home, preferably by walking, wheeling, cycling (active travel), or using public transport options.

(2) 4.4 To minimise carbon emissions, new development will be guided to locations that help to reduce the overall need to travel, offer the best opportunity for active travel, and for the use of public transport. This will help to maximise opportunities for sustainable travel and reduce the reliance on and for minimal use of private motor vehicles.

4.5 By integrating design-led approaches and placemaking principles into all aspects of community planning and development, the Live Well Locally concept aims to create neighbourhoods that are not just physically appealing, but also capitalise upon a local community's assets, inspiration and potential to foster a sense of belonging, identity, and shared experience.

(4) 4.6 The Live Well Locally policies have utilised the following national guidelines to create bespoke policies to meet Rother's situation:

- 'Building for a Healthy Life' (BHL) (June 2020) is the new name and edition of 'Building for Life 12', a Government-endorsed industry standard for well-designed places. Written in partnership with Homes England, NHS England and NHS Improvement, BHL consists of a series of considerations designed to help structure discussions between local communities, local planning authorities, developers and other stakeholders, and to help local planning authorities assess the quality of proposed and completed developments.

- 'ATE Planning Application Assessment Toolkit' (May 2023) was published by Active Travel England. It helps to assess the active travel merits – walking, wheeling and cycling – of a development proposal. Active Travel England's has an overall objective for half of all journeys in towns and cities to be cycled or walked by 2030, transforming the role that walking and cycling play in England's transport system and making it a great walking and cycling nation.

- 'Active Design' (May 2023) was published by Sport England with support from Active Travel England and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. It encourages the creation of environments that enable individuals and communities to lead active and healthy lifestyles. It shows how good design and place-making can make active choices easy and attractive.

(2) 4.7 The design of new development must therefore address both strategic placemaking (spatial patterns of growth, location of development) as well as site specific placemaking by reference to detailed design considerations at a site, development and building level.

(2) 4.8 In assessing the suitability of a particular location for development, when both allocating land for development and determining planning applications, sites and/or proposals must accord with the relevant policies of this Local Plan and meet the following strategic placemaking policies:

- Facilities and Services (Policy LWL2)

- Walking, Wheeling, Cycling & Public Transport (outside the site) (Policy LWL3)

4.9 All development proposals for more than one dwelling or 100sqm of floorspace, must accord with the relevant policies of this Local Plan and must meet the following site-specific placemaking policies:

- Compact Development (LWL1)

- Walking, Wheeling, Cycling & Public Transport (within the site) (Policy LWL4)

- Distinctive Places (Policy LWL5)

- Built Form (Policy LWL6)

- Streets for All (Policy LWL7)

- Multimodal Parking (Policy LWL8)

(5) Proposed Policy LWL1: Compact Development

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

Proposals for new residential development must contribute to achieving well-designed, attractive, and healthy places that make efficient use of land and deliver appropriate densities. The following density ranges, expressed as dwellings per hectare (dph), will apply to different area types, as defined by Rother's Density Study:

- Urban areas in Bexhill, Battle and Rye: 60-90+ dph, with higher densities around transport hubs and town and district centres.

- Suburban areas in Bexhill, Battle, Hasting Fringes and Rye: 45-75 dph.

- Live well locally areas: 45-60 dph.

- Village areas (with development boundaries): 25-45 dph.

- Countryside areas (including villages and hamlets without development boundaries): in the instances where residential development is supported by policies in this plan, the density should reflect the existing character of the area.

Development proposals must meet the minimum density in the ranges above, unless there are overriding reasons concerning townscape, landscape character, design, and environmental impact. This will support a critical mass for multiple local services/facilities and the viability of public transport including Demand Responsive Transport (DRT), shuttle bus services and car clubs.

Densities more than the maximum will be encouraged within these zones where the development is the result of a robust high-quality design-led approach; there is good access to shops, services and public transport connections; and/or the proposals are in accordance with a neighbourhood plan, design code or other adopted policy guidance.

Explanatory Text:

4.10 In preparing the new local plan, our approach has been to divide Rother into area types. These area types are areas of similar character that allow elements of policy to be set out depending upon which area type a development is within. While most local plan policies will apply to the entire district, some elements of policy will apply to types of area, for example all villages with development boundaries, or all suburbs. The area types identified in Rother are:

- Urban areas

- Suburban areas

- Live well locally areas

- Village areas (with development boundaries)

- Countryside areas (including villages and hamlets without development boundaries)

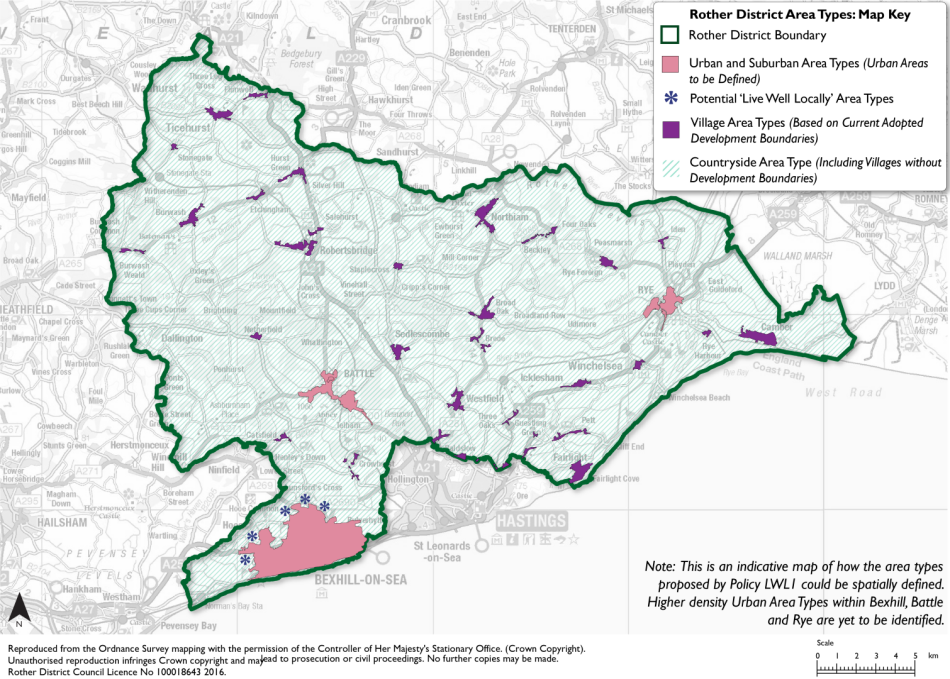

4.11 Figure 8 shows the distribution of the area types throughout the district. The settings for each of the area types has been based on an analysis of the existing character of these areas and a visioning exercise. The aim of the local plan policies is to work towards a future enhanced vision of what each area type needs to be.

(3) Figure 8: Proposed Density Areas

(1) 4.12 Efficient use of land is a key aspect of well-designed new developments and a requirement of the NPPF[17]. A compact form of development is more likely to accommodate enough people to support shops, local facilities, and viable public transport, maximise social interaction in a local area, and make it feel a safe, lively, and attractive place. This can help to promote active travel to local facilities and services, reducing dependence on the private car.

(2) 4.13 Density is one indicator for how compact a development or place will be and how intensively it will be developed. Ranges of density allow for local variations in density, which may be desirable to create a variety of identity without harming local character as set out in Historic England guidance. Additionally, compact development has several benefits such as minimising traffic, supporting transit, improving air quality, preserving open space, supporting economic vitality, creating walkable communities, and providing a range of housing options.

Regulation 18 Commentary:

4.14 Figure 8 is an indicative map of how the area types proposed by Policy LWL1 could be spatially defined. Higher density Urban area types within Bexhill, Battle and Rye are yet to be identified. 'Live Well Locally' area types will be defined through local plan site allocations and are likely to relate to the proposed growth areas identified in the development strategy. These areas are in West and North Bexhill.

4.15 The identification of the Suburban and Urban area type boundaries within Bexhill, Battle and Rye will be defined following further work, through a combination of characterisation studies, Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis, the experience of planning officials, local communities, and responses to consultation.

Question Box

(35) 27. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on compact development?

(23) 28. What are your views on the area types and densities proposed as a key driver to Live Well Locally?

(8) 29. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(7) Proposed Policy LWL2: Facilities & Services

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

(A) All development proposals for one or more new dwellings must meet the following criteria:

- Accessible Centres.

In Urban, Suburban and 'Live Well Locally' Area types, be located within an 800m safe, usable walking distance of a mix of local amenities (either within the site or outside but accessed via an accessible walking network) appropriate to the development proposed. Examples of local amenities include:

- A food shop which sells fresh fruit and vegetables.

- A park or green space.

- An indoor meeting place (pub, cafe, community centre, place of worship)

- A primary school

- A post office or bank

- A GP surgery

In Village and Countryside Area Types be located within an acceptable safe, useable walking or cycling distance of the listed mix of local amenities. This may be more than 800m.

Where a mix of local amenities are not accessible by walking and cycling, development must be located on safe, useable walking routes, that are an appropriate distance to a suitable bus stop facility, served by an appropriate public transport service(s), which connects to destination(s) in a site's respective sub-area that contains the remaining local amenities.

- Public Squares and Spaces. Provide, or contribute to, a connected and accessible network of safe, attractive, varied public squares and open spaces with paths and other routes into and through, places to rest and interact e.g. benches and other types of seating and provide good signage and wayfinding that is accessible to all. This should form part of a wider connected accessible Green Infrastructure network which includes food growing opportunities (allotments and community gardens) and prioritises locally native plant species.

- Play, Sports, Food Growing Opportunities and Recreational Facilities. Provide, or contribute to, play, sports, food growing opportunities and other recreational facilities that must not be hidden away within developments but located in prominent safe, secure, overlooked locations that can help encourage new and existing residents of all ages and abilities to share a space. Whether public or privately managed there must be well considered management arrangements and a long-term maintenance plan.

(B) All development proposals of 150 dwellings or more must meet the following criteria:

- Indoor Meeting Place. Either by upgrading existing facilities, such as school or village halls, or by contributing to a new facility, provide a digitally connected, flexible and multifunctional indoor place that meets the needs of the community and is suitable for co-working, hosting events such as markets, training and to supports social prescribing.

Explanatory Text:

4.16 Live well locally is a variation of the 20-minute neighbourhood concept that adapts to Rother's local context, including its dispersed settlement pattern. The 20-minute neighbourhood concept suggests that people of all ages and abilities should be able to reach their daily needs (such as housing, work, food, health, education and culture and leisure) within a 20-minute walk or bike ride, to reduce reliance on the car. This concept is also known as complete, compact, and connected communities.

(3) 4.17 Live well locally seeks to build upon existing transport networks (where they exist), such as bus and rail services, demand responsive solutions, social care, education, and community transport. It promotes new and emerging modes such as community car and bike share, offering alternatives to car ownership.

(3) 4.18 Many communities in Rother have community and church halls, shops, village squares, healthcare facilities, pubs, and other amenities. These can all help provide focus for the live well locally community concept by becoming 'neighbourhood activity centres' and/or 'mobility hubs', providing information services and infrastructure as well as wider community-based services in an indoor meeting place.

4.19 The more rural parts of Rother, many people face difficulties in reaching essential services and opportunities. We recognise that rural communities have different needs and preferences for connecting to surrounding places and car use can be necessary.

4.20 This policy, and the live well locally concept, aims, over the lifetime of the plan, to connect dispersed healthcare, retail, education, and leisure facilities so that more people of all ages and abilities have easier access, as well as to improve connectivity to local jobs and the higher-level services that are only available in the larger towns.

Question Box

(34) 30. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on facilities and services?

(17) 31. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(18) 32. Specifically, what are your views on the proposed mix of local amenities and the requirement, within certain area types, for new development to be located within an 800m walk of these amenities?

(10) Proposed Policy LWL3: Walking, Wheeling, Cycling and Public Transport (Outside the Site)

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

(A) All major development proposals for new dwellings must meet the following criteria:

- Access and Provision of Public Transport. Be located on sites that have access to effective and convenient public transport, particularly in relation to scheduled bus routes to train stations, but also through, Demand Responsive Transport (DRT) or shuttle bus services. This must be either through proximity to existing routes or through the provision of new or extended routes, within a 400m walking distance of all properties.

- Active Travel Infrastructure. Provide or financially contribute to the delivery of walking, wheeling and cycling (active travel) infrastructure, integrating with any applicable Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans and the East Sussex Local Transport Plan, evidenced through the submission of a Transport Assessment that:

- Provides a quantitative analysis of the multi-modal trip generation of the development, considering the routing of these trips to inform further considerations about the impacts and quality of existing routes within and outside the development.

- Provides qualitative analysis of the accessibility of the site for all users particularly those most vulnerable e.g. older people, young and disabled and highlight deficiencies and opportunities in surrounding walking, wheeling, and cycling infrastructure through consideration of policy and guidance provided in CIHT 'Planning for Walking' 2015, LTN 1/20[18] and Active Travel England's active travel design tools. Development should consider new guidance and tools, as issued by Active Travel England as they become available.

- Provides detail and justification of proposed improvements to infrastructure and any other supporting strategies which seek to enable an increase in walking, wheeling, and cycling rates for all users particularly the most vulnerable.

- Provides a quantitative analysis of the multi-modal trip generation of the development, considering the routing of these trips to inform further considerations about the impacts and quality of existing routes within and outside the development.

Facilities at bus stops and rail stations must already exist (or be provided) that enable ease of access by active travel modes, for all users, to public transport so as to create mobility hubs, including:

- Secure and overlooked cycle parking and facilities (including hire).

- Seating provision.

- Lighting.

- Adequate shelter to accommodate likely demand.

- Service information (including RTI).

- Raised kerb and dropped kerb access at bus stops.

- Appropriate signage and wayfinding.

- Electric charging.

- Parcel collection.

- Coastal Access. Public access to the coast must be retained and improved where possible (e.g., through the creation of new path links). The King Charles III England Coast Path National Trail must be protected and opportunities taken to enhance the route (e.g., re-aligning the trail closer to the sea).

(B) All development proposals of more than 50 homes must meet the following criteria:

- High-quality Walking and Wheeling Routes. Provide (if they do not already exist) a high-quality walking and wheeling route from the site to:

- A transport node (a regular public transport service which enables people to carry out daily duties such as employment and education);

- A primary school (if applicable);

- A shop selling mostly essential goods or services which benefit the community e.g., medical services; and

- Open green or blue space.

Reference should be made to the latest version of 'Manual for Streets' (DfT) and 'Designing for Walking' (Chartered Institution of Highways & Transportation) and Active Travel England's active travel design tools for details but, as a minimum, a route must:

- Be 2m wide (with limited pinch points of 1.5m due to street furniture) and localised widening to accommodate peak usage.

- Step-free.

- Have a smooth, even surface.

- Have street lighting in line with the Institution of Lighting Professionals Towards a Dark Sky Standard.

- Include appropriate crossings in compliance with standards set out in LTN 1/20 and Inclusive mobility.

- Have frequent seating provision.

- Have navigable features for those with visual, mobility or other limitations.

- Routes incorporating 'Greenways', 'Quietways' and upgrades to existing or the provision of new Public Rights of Way (PROW) will be supported and encouraged.

- Cycle Routes to Key Destinations. Provide off-site routes that consider compliance with LTN 1/20 and Active Travel England's active travel design tools to relevant destinations such as schools, local centres, employment centres, railway stations and the existing cycling network. All new or improved off site routes must be safe for cyclists of all abilities, ages, and mobility needs.

Explanatory Text:

4.22 Locating development to enable people to live and work locally can encourage economic participation and improve health and wellbeing through better air quality, more physical activity, and social interaction, which will be particularly beneficial for Rother's ageing population.

(1) 4.23 As a predominantly rural district, where there is a high reliance on the private car, creating a pattern of development which contributes to residents being able to travel less between homes, services, and jobs, makes efficient use of existing networks, promotes active travel, increases opportunities for those without or unable to use a car, improves mental and physical health and can also support decarbonisation. Some people will still need to drive, but the focus will be on reducing reliance on the car and supporting the transition to ultra-low and zero-emission vehicles through the provision of suitable refuelling and charging infrastructure.

(1) 4.24 New development should exploit existing (or planned) public transport hubs, such as train stations and bus interchanges, walking and cycling routes, to build at higher densities and channel a higher percentage of journeys to public transport.

(1) 4.25 Opportunities for enhanced sustainable transport measures are being considered through the Transport Assessment and Infrastructure Delivery Statement for the Local Plan. This will help to identify wider solutions and appropriate mitigation for development and look comprehensively at a package of measures that could be delivered to support the Council's emerging growth strategy and the ambitions of the Climate Strategy 2023. As the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) Net Zero Transport research paper mentions, in the longer term, further collaboration between the transport and land-use planning sectors will help to achieve carbon reduction/net zero targets and benefit the health and wellbeing of residents.

4.26 Public transport must be accessible within a 400m walking distance of all properties either through proximity to existing routes or through the provision of new or extended routes. On developments of 50 homes or more or 500sqm or more of non-residential floorspace, at least one public transport service must be fully operational on the first day of occupation or in accordance with the phasing of the development. (Including Demand Responsive Transport (DRT) or shuttle bus services).

(1) 4.27 The highway authority produces Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans (see NPPF, paragraph 110d). If there is an existing protected cycle network, new development should connect to it. Alternatively, large new development should begin a new one by building or funding routes to key destinations.

4.28 Opportunities to deliver mobility hubs, as referred to in ESCC's Local Transport Plan 4 (LTP4)[19], should be considered in Transport Assessments. Appropriate facilities would depend on whether the hub is a large transport interchanges (i.e. rail or bus stations) or a bus stop or a town or village centres.

(2) 4.29 Wheeling is a term that refers to a type of mobility that is equivalent to walking, but uses wheeled devices such as wheelchairs, mobility scooters, or other aids. Wheeling does not include cycling unless the cycle is used as a mobility aid by someone who cannot walk or push their cycle. Wheeling covers modes that use pavement space at a similar speed to walking.

4.30 Short trips of up to three miles, can be easily made on foot or bicycle if the right infrastructure is in place, helping to improve public health and wellbeing and air quality whilst also reducing local congestion and carbon emissions and increasing opportunities for all to access key services, employment, and education. The National Travel Survey of 2018 identified the average number of cycle trips made per person was 17, with average total miles cycled per person 58. So, the average journey is 3.4 miles.

(1) 4.31 All new development must ensure access for all and help make walking and cycling feel like the natural choice for everyone undertaking short journeys (such as the school run or older generations accessing local facilities and services) or as part of longer journeys.

Question Box

(28) 33. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on walking, wheeling, cycling and public transport (outside the site)?

(17) 34. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(14) 35. Specifically, what are your views on the requirements set regarding public transport, such as the 400m walking distance proximity requirement?

(2) Proposed Policy LWL4: Walking, Wheeling, Cycling & Public Transport (Within the Site)

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

All development proposals for one new dwelling or more must meet the following criteria:

- Connecting Beyond the Site. Anticipate and respond to pedestrian and cycle 'desire lines' (the preferred route a person would take to travel from A-to-B). This may include the improvement of existing public rights of way.

- Connected Streets, Paths, and Routes.

- Use simple street patterns based on formal or more relaxed grid patterns.

- Use straight or nearly straight streets to make pedestrian and cycle routes as direct as possible.

- Continuous streets (with public access) along the edges of a development. Cul de sacs will not be supported where there are opportunities to create connections.

- Site Permeability. Routes for walking, wheeling and cycling that are shorter and more direct than the equivalent by car. This could be achieved by 'filtered permeability'.

- Walking, Wheeling and Cycling Access. Maximise all opportunities for safe, step-free, fully accessible walking, wheeling, and cycling site access points and be greater in number than the number of access points for motor vehicles (except where additional accesses would provide no benefit to people walking, wheeling, or cycling). A motor vehicle access point with safe provision for both walking, wheeling and cycling counts as a walking, wheeling and cycling access point.

- Safe Routes Accessible to All. Walking, wheeling and cycling routes which are fully accessible to all users and:

- Prioritise safety by being overlooked wherever possible and be adequately lit at night in accordance with LTN 1/20 and Active Travel England's active travel design tools.

- Provide frequent benches along all pedestrian routes to help those with mobility difficulties walk more easily between places.

- Provide navigable features for those with visual, mobility or other limitations.

- Through Traffic. Site accesses arranged to prevent private vehicle drivers from using the site as a shortcut while undertaking a longer journey. This is best achieved through filtered permeability, or by ensuring all general traffic accesses are taken from the same main road.

- Safety At Junctions. All new or improved on-site junctions (including the site access) LTN 1/20 compliant, adhering to Active Travel England's active travel design tools and designed in line with the movement hierarchy: pedestrians, followed by cyclists, public transport users and private motor vehicles.

- Crossings. The appropriate crossing type (signalised / zebra / uncontrolled / continuous footway) provided along forecasted desire lines and compliant with standards set out in LTN 1/20, Inclusive Mobility and Active Travel England's active travel design tools.

- Shared Use Routes. Protected cycle ways provided along busy streets. Shared use routes (i.e., a path or surface which is available for use by both pedestrians and cyclists) avoided along all new or improved streets with the site, unless they fit in the limited acceptable situations listed in LTN 1/20.

- Future Expansion. Enable and propose the adoption of walking, wheeling and cycling routes up to the site boundary to provide direct connections to existing or future development where sites are either anticipated, planned, proposed, or allocated through the local plan.

- Shared Mobility. Integrate provision of infrastructure for Demand Responsive Transport, car clubs and car shares as well as Park and Ride schemes, if introduced.

- Zero Emission Vehicles. Integrate provision of infrastructure for rapidly advancing electric car and other zero emission technology.

Explanatory Text:

4.32 Streets and routes must connect people to places and public transport services in the most direct way, making car-free travel more attractive, safe, and convenient and accessible for all.

4.33 Streets and routes must pass in front of people's homes rather than to the back of them creating a well overlooked public realm.

4.34 "Filtered permeability" is a concept that relates to the ease with which different modes of transportation (e.g., walking, cycling, wheeling, public transport, and driving) can move through and access different parts of an area. It refers to the idea of selectively allowing or promoting certain types of transportation while discouraging or hindering others in a way that supports sustainable and efficient mobility.

(3) 4.35 Filtered permeability encourages and prioritises sustainable modes of transportation, such as walking and cycling. This means designing places that make it easy and safe for pedestrians and cyclists to move through the environment.

4.36 The goal of filtered permeability is to create a more sustainable and efficient transportation system by making sustainable modes of transportation more attractive and car use less convenient, especially in areas where people live, work, shop and go to school. This approach can help reduce traffic congestion, lower emissions, and improve quality of life.

Question Box

(15) 36. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on walking, wheeling, cycling and public transport (within the site)?

(6) 37. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(11) 38. Specifically, what are your views on the provision of Demand Responsive Transport, car clubs and car shares?

(4) Proposed Policy LWL5: Distinctive Places

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

All development proposals for one or more new dwelling must meet the following criteria:

- Response To Site, Character and Landscape Context. Demonstrate a clear understanding of the context and landscape character (including townscape) of the site and beyond. New development must conserve, enhance, and draw inspiration from this context and character in either a traditional or contemporary style. The use of standard building or house types that take no account of local character, bad imitation of traditional design or simply replicate generic or mediocre design in the locality will not be acceptable.

- Design Concept. Be visually attractive and be informed by a clear rationale and strong design concept developed in response to an understanding of the context and landscape character (including townscape). The design concept must also inform a consistent choice of high-quality materials, finishes, detailing and landscape design. Generally, unprepossessing late twentieth century and twenty-first century development in the area should not be used as precedents for material and finishes choices in new development.

- High Weald National Landscape. All development within or affecting the setting of the High Weald National Landscape shall conserve and enhance its distinctive landscape character, ecological features, settlement pattern and scenic beauty, having particular regard to the impacts on its character components, as set out in relevant policies in this plan, the latest version of the High Weald National Landscape Management Plan and the High Weald AONB Design Guide and Colour Study.

- Material Banks for Future Development. Building materials are valuable resources to be conserved and reused. All development must incorporate design for disassembly principles, allowing for the efficient removal and recovery of materials when a building is no longer needed.

- Bioregional Design. All development must be produced in a way that suits the local area and its resources. We strongly encourage the use of low carbon materials, such as local and certified well-managed wood, for building structures, cladding and external works.

- Existing Assets. Use existing assets as anchor features, such as mature trees and capitalise on other existing features such as key views on or beyond a site.

- Futureproofing and Safeguarding. Ensure that land is reused/used efficiently, effectively, and must not prejudice existing and future development and connectivity to and from adjoining sites. Where such potential may exist, development must progress within a comprehensive design masterplan framework or enable a co-ordinated approach to be adopted towards the development of adjoining sites in the future.

- Stewardship. Demonstrate how they will achieve long-term stewardship of places (streets and spaces), community assets and green infrastructure by producing a Stewardship Plan that:

- Includes a clear management plan that sets out the vision, objectives, standards, and actions for the delivery and maintenance of places, community assets and green infrastructure, and how they will contribute to the social, economic, and environmental well-being of the community.

- Includes a clear participation strategy that sets out how the community will be involved in the design and management of places, community assets and green infrastructure, including the use of participatory methods, co-design, co-production, and co-management.

The Council will support proposals that adopt community stewardship models of governance, such as informal community management groups, neighbourhood planning groups, community management of public spaces, community management of buildings and facilities, community management of local energy networks, community land trusts and community housing such as cooperatives and co-housing, that give the community a key role and stake in the ownership and management of community assets and green infrastructure. The Council will also support proposals that reinvest the surplus generated by community assets and green infrastructure into the community, such as through community funds, grants, or dividends.

- Residential Assessment Frameworks. All residential development must address the 12 considerations of "Building for a Healthy Life", and its companion 'Streets for a Healthy Life', written in partnership with Homes England, NHS England, and NHS Improvement.

- All Development Assessment Framework. All development must address the ten principles of "Active Design", as published by Sport England and supported by Public Health England.

Explanatory Text:

4.37 New development should create places that are memorable, with a locally inspired or otherwise distinctive character.

4.38 If distinctive local characteristics exist, new development should delve deeper than architectural style and details. Where the local context is poor or generic, this should not be used as a justification for more of the same. Inspiration may be found in local history and culture.

(1) 4.39 Positive local character comes from: streets, blocks, and plots ('urban grain'), green and blue infrastructure, land uses, building form, massing, and materials. These characteristics often underpin the essence of the distinctive character of settlements rather than architectural style and details.

4.40 Using a local materials palette (where appropriate) can be a particularly effective way to connect a development to a place. This is often more achievable and credible than mimicking traditional architectural detailing which can be dependent on lost crafts.

4.41 Brownfield sites can offer sources of inspiration for new development. Greenfield and edge of settlement locations often require more creativity and inspiration to avoid creating places that lack a sense of local or otherwise distinctive character.

(1) 4.42 Character can also be created through the social life of public spaces. New development should create the physical conditions for activity to happen and bring places to life.

(1) 4.43 The pattern of development should protect and enhance the High Weald National Landscape, open countryside and protected ecological habitats.

(2) 4.44 Rother recognises the significance of promoting circular and sustainable practices in the construction and demolition industry. To reduce waste, preserve valuable resources, and contribute to a more sustainable environment, Rother encourages the design and construction of buildings with the potential to serve as material banks for future development projects. This will promote the reuse and recycling of building materials and reduce the environmental footprint of the construction sector. To meet this criterion, all development proposals of 50 dwellings or more or 500sqm or more of non-residential floorspace must submit a material recovery plan, as part of their planning application, outlining how materials will be disassembled, recovered, and stored for future reuse.

4.45 Bioregional design seeks to align development with the ecological and natural systems of the region, fostering a harmonious relationship between the built environment and the surrounding ecosystem. To meet this criterion, all development proposals of 50 homes or more or 500sqm or more of non-residential floorspace must submit a bioregional assessment, as part of their planning application, to optimise resource use and minimise waste through strategies such as sustainable water management, energy conservation, and the use of locally sourced materials.

4.46 Well-designed places sustain their beauty over the long term. They add to the quality of life of their users, and as a result, people are more likely to care for them over their lifespan. They have an emphasis on quality and simplicity. Places designed for long-term stewardship are robust and easy to look after, enable their users to establish a sense of ownership, adapt to changing needs and are well maintained.

4.47 Management and maintenance of places incorporate the processes associated with preserving their quality or condition. Good management and maintenance contribute to the resilience and attractiveness of a place and allows communities to have pride in their area.

4.48 Long term management plans for new development might include individual residents and businesses managing private space, adoption by a public authority, the use of management companies or management by the community.

4.49 Processes of participation, consultation and co-design improve transparency, help to build trust, allow for valuable local knowledge to be gained, increase a sense of ownership over the completed development and help to build community cohesion.

4.50 Community management is the management of a common resource by the people who use it through the collective action of volunteers and stakeholders. The community management of neighbourhoods is a valuable way of engendering a sense of ownership and responsibility as well as building social cohesion.

4.51 Residential development proposals will be expected to show evidence of how their development performs against the Building for a Healthy Life considerations. There is no obligation on applicants to use an external or independent consultant to complete an assessment, but they are free to do so if they so wish.

Question Box

(17) 39. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on distinctive places?

(7) 40. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(6) 41. Specifically, what are your views on using the considerations in Building for a Healthy Life and Streets for a Healthy Life as a framework for assessing residential development?

(4) Proposed Policy LWL6: Built Form

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

(A) All development proposals for one or more new dwellings must meet the following criteria:

- Landscape Strategy. The landscape strategy must help determine the capacity of the site and hence the appropriate developable area for the development. All layout or landscape plans for multiple unit or large building developments must have accurate contour plans and information about surface water flows. Single dwelling proposals must have levels on the site and contours for the site context clearly shown on relevant plans.

- Orientation. Provide evidence of how the orientation of buildings and streets has taken account of:

- What is locally characteristic; (through an analysis of the existing site, context and landscape character, including townscape).

- Microclimate.

- Opportunities to maximise passive solar gain and roof-mounted energy collection, while ensuring against excessive internal heat gains in warmer seasons. New buildings and streets must prioritise southern exposure for passive heat gain, while minimising east-west orientation, (unless there are overriding reasons concerning context and landscape character).

- Key views and vistas.

- Topography and significant existing features.

- The need for natural surveillance.

- Legibility and Street Hierarchy. Promote good legibility in the following ways:

- Clear route hierarchy.

- Strong and logical building layout and massing.

- Consistent choice of materials.

- Use local landmarks and key views.

- Retention of key distinctive features.

- Perimeter Blocks. Aim to respect existing or achieve new perimeter block layouts unless not feasible or not locally characteristic. Utilise cohesive building compositions that define appropriate building lines and create consistent, visually harmonious street edges to enhance the pedestrian experience.

Non-residential developments that are delivered as a series of individual parcels with their own surface level car parks set back from the street will not be supported.

- Active Frontage. Streets must have active frontages with dual aspect homes on street corners with windows serving habitable rooms. Street corners with blank or largely blank sided buildings and/or driveways, street edges with garages or back garden spaces enclosed by long stretches of fencing or wall must be avoided. Windows must be clear along the ground floor of non-residential buildings (avoid obscure windows).

- Transitions. Transitions between existing and new development must be sensitive and well considered so that building heights, typologies and tenures sit comfortably next to each other.

- Edges. New settlement edges must look both ways, responding to the countryside while also knitting into the existing fabric of a settlement. Where possible, new development should address the countryside directly and not turn its back onto it, unless this is not locally characteristic.

(B) All major housing developments must have 50% of dwellings have a form factor of 1.7 or less to ensure that housing is designed to be energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable.

Explanatory Text:

4.52 Solar orientation has a critical role in creating energy-efficient and sustainable environments that are aligned with their climatic conditions. Integrating solar orientation principles into perimeter block design will maximize passive heat gain, enhance occupant comfort, and reduce energy consumption. By aligning building layouts with the sun's path, we can create resilient and energy-conscious communities.

4.53 The following generic principles for optimum solar orientation and form should be followed:

- Wide fronted units facing north or south should have a primary aspect within 30º of due south.

- East and west facing units should be within 30º of the north/south axis such that gabled roof profiles can present a major roof pitch to the south.

- Anticipating the need for electric vehicle charging, parking structures with roofs of 5º - 7º pitches can be used if aligned on the north/south axis and 30º pitch if aligned to face south.

- Use plot disposition and building placement to support solar gain from the South, and to minimise left over space.

- For optimising intelligent solar design, use of wide fronted dwelling typologies are appropriate when aligned to east-west oriented roads whereas narrower and deeper plans may be appropriate to line north-south oriented roads.

- For optimising intelligent solar design, primary roof pitches to face within 30º of due south and special care is needed to avoid overshading from other buildings and vegetation (bear in mind growth over time).

- Simple roof forms allow for maximising energy collection whereas use of hips, valleys and dormers tend to limit this potential.

4.54 A building's form factor is the ratio of its external surface area (i.e., the parts of the building exposed to outdoor conditions) to the internal floor area. The greater the ratio, the less efficient the building and the greater the energy demand. Detached dwellings will have a high form factor, whereas apartment blocks will have a much lower form factor and thus will tend to be more energy efficient. The Climate Emergency Guide by LETI contains a list of typical form factors associated with different design configurations.

- Bungalow house – 3.0

- Detached house – 2.5

- Semi-detached house – 2.1

- Mid terrace house – 1.7

- End mid-floor apartment – 0.8

4.55 This means that half of the dwellings in new developments [over 10 dwellings] must be provided as terraces or flats. As an example, a 10 dwellings scheme might comprise a row of 5 terraced homes, a pair of 2 semi-detached dwellings and 1 detached residence. Such a mix would also be characteristic of the High Weald National Landscape where a typical grouping would contain a mixture of terraces, a detached cottage, and semi-detached dwellings.

Question Box

(14) 42. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on built form?

(5) 43. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(10) 44. Specifically, what are your views on prioritising solar orientation and form factor when designing new developments?

(3) Proposed Policy LWL7: Streets for All

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

(A) All development proposals must meet the following criteria:

- Design Speed of New Streets. New or improved streets designed (no centre line, horizontal deflection, narrow width) and signed for vehicles to travel at a max speed of 20mph.

- Shared Streets. Street space shared fairly between pedestrians, cyclists, and motor vehicles (See Manual for Streets User hierarchy) and be inclusively designed so that people with visual, mobility or other limitations will be able to use the street confidently and safely. Incorporate a variety of street furniture (e.g., benches, places to sit, rest and interact), sensitively and appropriately located at regular intervals, along with good signage and wayfinding that is accessible to all to encourage walking and prioritise vulnerable users.

They must be adopted, managed, and resourced as public open space rather than as public highway with its conventional emphasis upon motorised traffic movement.

- Dementia Friendly District. Streets and spaces designed to adhere to best practice 'designing for dementia' principles, to contribute towards making Rother's outdoor environments more age and dementia-friendly.

- Use Buildings to Define Streets & Spaces. Well defined new streets and spaces enclosed by buildings or landscape elements, particularly street trees, and boundary structures.

- Tree Lined Streets. For cooling and carbon capture, with appropriate native and climate resilient trees that are in the public realm rather than on private property, have a wider canopy form for cooling and shade, have sufficient space to grow above and below ground and have long term management arrangements in place.

- Animated Streets. Create animated streets, incorporating public art, cultural installations, street furniture and heritage features to enrich the visual appeal and cultural identity of public spaces.

- Landscaping. Provide landscape layers that add sensory richness to a place – visual, scent and sound and help settle parked cars into the street. With frontage parking, the space equivalent to a parking space must be given over to green relief (for instance every four bays). Areas identified as suitable for growing fruit and vegetables within the curtilage of the street or public courtyards will be supported.

- Sustainable Drainage Systems. Incorporate sustainable drainage systems (SuDS), such as swales, rain gardens or ditches as well as infiltration zones such as grass verges, into streets.

- Services. Incorporate all underground surfaces into shared trenches with common ducting where possible. This must be considered at an early stage in the design layout and be designed to be compatible with Green Infrastructure and Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS). Landscape elements such as street trees must not be prejudiced by lighting columns or underground ducting.

- Reducing Street Clutter. Streamline the placement of signage, street furniture, and other elements in public spaces to reduce street clutter. Benches and bins must be consistent with the design concept for the site/development.

- Healthy Streets. Address the ten 'Healthy Streets' indicators of the "Healthy Streets Toolkit," as endorsed by the East Sussex LTP4.

- Historic Streets. Address the guidance in "Streets for All: Advice for Highway and Public Realm Works in Historic Places," as published by Historic England, where relevant to the context.

(B) All development of 150 dwellings or more or 15,000sqm or more of non-residential floorspace must meet the following criteria:

- Meaningful Variation Between Street Types. Use a street hierarchy to help people find their way around a place. For instance, principal streets can be made different to more minor streets using different spatial characteristics, building typologies, building to street relationships, landscape strategies and boundary and surface treatments.

Explanatory Text:

4.56 Streets are different to roads. Streets are places where the need to accommodate the movement of motor vehicles is balanced alongside the need for people to move along and cross streets with ease. Activity in the street is an essential part of a successful public realm.

4.57 Streets should be designed to meet the needs of the whole community, be attractive, create a sense of place, pride and enable healthy lifestyles. A strong framework of connected healthy streets improve people's physical and mental health. Encouraging walking, cycling, outdoor play and streets where it is safe for younger children to cycle (or scooter) to school can create opportunities for social interaction and street life bringing wider social benefits. It is important to avoid streets that are just designed as routes for motor vehicles to pass through and for cars to park within.

4.58 Front doors, balconies, terraces, front gardens, and bay windows provide active frontages and are a good way to enliven and add interest to the street and create a more human scale to larger buildings such as apartments and supported living accommodation.

4.59 As the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) Dementia and Town Planning research paper mentions, well planned, enabling local environments can have a substantial impact on the quality of life for someone living with dementia, helping them to live well in their community for longer. An overriding principle of this advice is that if you get an area right for people with dementia, you can also get it right for older people, for young disabled people, for families with small children, and ultimately for everyone. Dementia-friendly environments are spaces that are designed to support the needs and preferences of people living with dementia. They aim to promote independence, wellbeing, safety, comfort, and meaningful activities for people with dementia and their carers. Easy access and wayfinding can help people with dementia to navigate an environment without getting lost or confused. This can include clear and consistent signage, landmarks, lighting, and contrast. Safety, security, and comfort helps people with dementia feel relaxed and calm in an environment. There are many resources and guidelines available that can help to design and evaluate dementia-friendly environments.

4.60 Different street types, along with buildings, spaces, non-residential uses, landscape, water, and other features can help people create a 'mental map' of a place. Streets with clearly different characters are effective in helping people grasp whether they are on a principal or secondary street. For larger sites, it will be necessary to use streets and spaces with different characters to help people to find their way around.

4.61 Large gaps in the street create 'leakage' of space and diminish sense of enclosure which may not be appropriate in more urban areas or in village centres. The opposite may apply, with large green gaps between buildings, in more rural locations where this is the established street character.

4.62 Sustainable drainage systems, commonly referred to as SuDS, provide an improved approach to the management of surface water runoff from hard surfaces such as roofs and car parks by replicating natural processes. Compared with traditional engineered drainage systems, SuDs can maximise the additional benefits that can be achieved by reducing site-based, local, and catchment-wide flood events. They allow ground water recharge which reduces water pollution, enhance biodiversity, and provide landscape amenity enhancement.

4.63 All development proposals must create animated streets. Where development proposals are for more than 50 dwellings or 500 sqm of non-residential floorspace, streets must provide places to sit, space to chat or play within new streets, as well as allow for temporary closures to maximise a streets multipurpose potential for other uses e.g., markets, festivals, parades etc.

4.64 While signage, street furniture, and other structures are vital to the successful design of public spaces, poor design leads to clutter which can have a detrimental impact on the environment. All development proposals must demonstrate how they avoid street clutter. Where development of 50 dwellings or more or 500sqm or more of non-residential floorspace. is proposed, it is recommended that the following approach is taken:

- Conduct a comprehensive inventory of all existing street clutter, including signage, utility poles, street furniture, and other elements that obstruct public spaces.

- Develop clear design standards and guidelines for street furniture, signage, and other streetscape elements that are consistent with the developments design concept.

- Consolidate and rationalize signage to reduce duplication and ensure that signs are clear, legible, and necessary.

- Encourage the undergrounding of utility lines where feasible to eliminate overhead clutter.

- Ensure the design and materials of bin storage areas, structures and pick up locations are well integrated secure, safe and overlooked.

- Ensure all services and access covers are integrated into the overall landscape design and not fitted as afterthoughts.

- Implement clear and consistent wayfinding systems that guide pedestrians and motorists without the need for excessive signage.

Question Box

(22) 45. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on streets for all?

(9) 46. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(5) 47. Specifically, what are your views on using the ten 'Healthy Streets' indicators of the 'Healthy Streets Toolkit' when designing new streets?

(3) Proposed Policy LWL8: Multimodal Parking

Policy Status:

Strategic

New Policy?

Yes

Overall Priorities:

Live Well Locally

Policy wording:

All development proposals must meet the following criteria:

- Cycle Parking. Provide cycle parking ensuring all users feel safe, consistent with the overall design concept for the site/development and provided in line with Table 11.1/Table 11.2 of LTN 1/20 (inc. requirement of 5% of spaces to be accessible for larger cycles).

- Residential Cycle Parking. Secure, covered, well-lit cycle storage for all new dwellings, including flats, must be located close to people's front doors so that cycles are as convenient to choose as a car for short trips and easily accessible from the dwelling.

- Non-residential cycle Parking. Secure, overlooked, well-maintained, well-lit cycle parking must be located closer to the entrance of schools, economic, leisure and community facilities than car parking spaces or car drop off bays, except for blue badge spaces. Facilities must be suitable for a range of cycle types including electric bikes, cargo bikes, tandems, and tricycles. Where appropriate, secure external cycle parking must be provided where off-street parking does not exist.

- Car Parking Layout. The proposed street design and parking management strategy demonstrably and physically discourage the blockage of footways, crossing points, sightlines, and cycle routes on and off site by indiscriminate and obstructive car parking.

- On Street Parking.

- Well integrated car parking design, with good landscape treatment avoiding a public realm dominated by cars, hard standing, too many materials and associated clutter. A parking strategy must inform the design layout from an early stage.

- Landscape-led design with layout and materials responding to the landscape character of the place.

- Maximise opportunities for enhancing green infrastructure and sustainable drainage.

- Minimise opportunities for anti-social car parking on pavements and green spaces.

- Be safe, conveniently located for the dwellings they serve, overlooked and accessible for all.

- In Curtilage Garages. Use limited on multi home developments.Repeated garages taking a large proportion of the ground floor frontage of a street avoided as this leads to a lack of fenestration and street animation.Garages which are designed to accommodate bicycles should meet minimum dimensions to ensure they can be accessed without the need to remove vehicles.

- In Curtilage Parking.

- Where in-curtilage parking for individual houses is to be used, car spaces must be to the side of the main building and at least 5.5m behind the building's front edge to prevent the vehicle protruding.

- In-curtilage parking in front of narrow-fronted properties should be avoided if better alternatives are available and where unavoidable must be restricted to two adjoining properties to reduce the visual impact of parked vehicles on the street scene.

- Drive widths must be at least 3.2m when also serving as the main pathway to the property.

- Private car spaces and drives visible from the street should be surfaced in small unit permeable pavers, or other materials (such as gravel) which will allow sustainable drainage, raising the environmental quality of the scheme.

- Car Parking Courts. Rear car parking courts serving houses must be avoided where possible.

- Allocations. Where possible, street, and shared court car parking should not be allocated to individual properties as this is a much more efficient use of space.

- Parking Squares. Parking squares designed with robust materials to function as attractive public spaces which also accommodate parked cars. This can be achieved with generous and appropriate green infrastructure, surfaces other than tarmac and appropriate street furniture.Parking squares should aspire to also be attractive areas of multi-functional public space, providing opportunities for communal activities such as market stalls, ceremonies, events, the annual Christmas tree.

- Communal 'Remote' Car Parking.

- Car parking can be partly or wholly located in well-designed communal blocks, such as car barns or car ports, preferably still with some natural surveillance.

- These communal blocks must be located within a short and convenient walking distance of the buildings it serves.

- Where 'remote' car solutions are used, streets and spaces closer to homes must be designed to make uncontrolled car parking less easy, to discourage antisocial car parking behaviour.

- Provision for disabled drivers, activities such as dropping off passengers and shopping and access for emergency vehicles, waste collection, bulky deliveries and removals to homes will still need to be fully considered.

- Green Infrastructure. Most car parking solutions will require generous green infrastructure, such as trees or rain gardens, to mitigate the visual impacts, maximise opportunities to enhance wildlife and provide shade.Too many materials, colour changes and small areas of kerbing and planting leads to an over busy result. Simple palettes and layouts are generally encouraged.

- Rural Car Parking.

- The design of car parks in the countryside or on the settlement edge must ensure they integrate into the surrounding landscape and avoid unwelcome visual impacts and suburban character.

- The layout, scale, materials, and mitigation measures using green infrastructure must be landscape-led and aim to enhance local character.

- Over-large car parks should be avoided where possible as they will conflict with local character and their visual impacts are more difficult to mitigate.

- Simple materials, based on what is locally characteristic, an absence of highway elements such as kerbs and clutter and locally appropriate planting represent the best approach in most locations.

- Other Parking. Provide safe, secure parking to support the use of powered two-wheelers. Facilities, with an electricity supply, must be suitable for a range of types including mopeds, scooters, and motorbikes.For specialist accommodation for older people and for people with disabilities, secure storage space under cover, with an electricity supply, is also required for powered wheelchairs or mobility scooters.

Explanatory Text:

4.65 Well-designed developments will make it more attractive for people to choose to walk or cycle for short trips helping to improve levels of physical activity, air quality, local congestion, and the quality of the street scene. Well-designed streets will also provide sufficient and well-integrated car parking.

4.66 Cycle parking in residential development should be designed to make it at least as convenient and attractive for residents to use cycles as a car when making local journeys. Storage should be as near to the street as possible. This could be integrated into the main building, in garages or in bespoke standalone storage, if located discreetly.

4.67 The most traditional car parking method is to provide unallocated spaces parallel with the street. This enables every space to be used by anyone and to its greatest efficiency. It often allows residents to see their car from the front of their house and contributes to an active street and traffic calming, while keeping most vehicular activity on the public side of buildings.

4.68 Parking bays which are perpendicular to, or at an angle to the street direction, can accommodate more cars than parallel parking spaces, but they increase the width of the road, they are potentially more dangerous (due to the need to reverse into traffic), and, if adjacent to homes, car lights can have a negative impact on the ground floor windows of habitable rooms at night.

4.69 Many modern residential developments provide in curtilage parking. This may provide the car-owner with greater security and ease of access, but it is a less efficient use of space than unallocated parking and prevents parking in the street across the access to the property.

4.70 Particularly when plot widths are narrow (below 6m) the parked car will usually visually dominate the front of the house. This effect will be magnified if this method is repeated at regular intervals in a street.

(2) 4.71 Garages are a very inefficient way of accommodating cars as research shows that only around half are used for that purpose.

4.72 Locating car parking at the rear of houses can lead to inactive frontages, discourage neighbourliness, walking and cycling and create safety and security problems both on the street and within the parking courtyards or unobserved garages. Furthermore, rear parking courts use land very inefficiently, often resulting in small gardens, reduced privacy, and parking by those without allocated rear spaces in inappropriate places.

4.73 Small squares can add interest and provide parking in a traffic calmed environment.

(1) 4.74 Car barns or car ports can effectively allow a low car, or even a car-free environment with all the benefits that can bring, particularly for residential areas. They are much more likely to be used than garages and can be a good way to integrate groups of cars into a landscape.

4.75 Rather than designing in car parking space that could become redundant as society evolves and possibly levels of car ownership drop, communal parking areas can easily be adapted to other uses in the future, if less space is required for private cars.

4.76 A combination of car parking approaches nearly always creates more capacity, visual interest, and a more successful place.

4.77 Some developments such as for economic, community or multi-residential uses will normally require significant car parking areas. These areas will need generous visual mitigation to reduce the impact of large numbers of vehicles and hard surfacing, but they also serve as significant opportunities to provide visual, functional, and ecological enhancements through generous green infrastructure (GI), including multifunctional sustainable drainage.

Question Box

(22) 48. What are your views on the Council's proposed policy on multimodal parking?

(6) 49. Are there any alternatives or additional points the Council should be considering?

(8) 50. Specifically, what are your views on communal 'remote' car parking?

[17] Paragraph 128, NPPF Dec 2023

[18] A local transport note (LTN), published in July 2020, that provides guidance to local authorities on delivering high quality, cycle infrastructure.

[19] The draft Local Transport Plan 2024-2050 (also known as LTP4) was at consultation stage at the time of publication of this draft.